New(ish) knee ligament

The paper: Claes, S. et al. (2013) Anatomy of the anterolateral ligament of the knee. J. Anatomy 223: 321-328. doi:10.1111/joa.12087

Subject areas: Anatomy

Vocabulary:

condyle – the round protuberance at the end of some bones, usually those that are part of a joint.

—–

This article is a summary of a recent primary research paper intended for high school teachers to add to their general knowledge of current biology, or to supplement their lessons by showing students the kinds of projects that current biological research addresses.

—–

There really isn’t a whole lot to this paper, but it is relevant, considering how many student-athletes have knee injuries every year. It is also interesting because it is hard to believe that after all this time, there are still structures in the human body that have not been discovered. If you think about all the medical students taking human anatomy, not to mention professors of anatomy, and the surgeons who work inside bodies, how could there still be anything left to discover?

The conventional assumption has long been that the knee joint is stabilized by four ligaments: the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments (ACL and PCL) that run inside the joint capsule and are the primary stabilizing ligaments connecting the femur to the tibia, and the medial and lateral collateral ligaments (MCL and LCL). The MCL connects the femur to the tibia and the LCL connects the femur to the fibula along the inside and outside aspects of the knee, respectively (medial means towards the center of the body, lateral means away from the center).

In the late 19th Century, a French surgeon by the name of Paul Segond, noticed a consistent fracture pattern at the anterolateral proximal tibia when the knee is forced to rotate too far inwards. He also noted a “pearly … fibrous band” at that area. However, because later work seemed to correlate the fracture pattern with ACL rupture, Segond’s fibrous band was mostly forgotten, although some anatomists noted a ligament in that position but assumed it to be part of another one, such as the LCL.

To more clearly define this possible ligament, the research team carefully dissected the knees of 41 cadavers ranging from 61-93 years old at death, roughly half men and half women. In all but one of the cadavers, there was clearly a small lateral ligament distinct from the other known structures around it, including the LCL. It is more clearly seen if the knee is partially bent (~60º angle) and the lower leg twisted inward slightly. This puts some stress on the ligament to make it stand out more. Because of the placement of the ligament, the authors have termed it the anterolateral ligament (ALL).

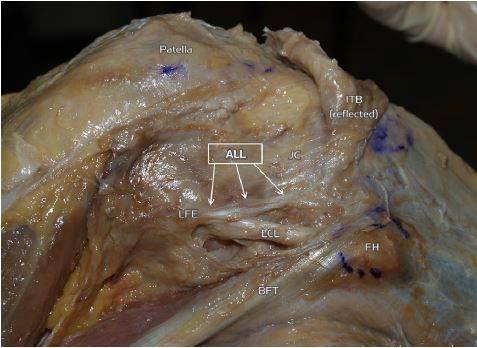

This is a right knee partially dissected in a bent position. The ALL is clearly visible and separate from the LCL. Other structures labeled are the lateral femoral epicondyle (one of the rounded ends of the femur), the biceps femoris tendon (BFT, tendons connect muscles to bone, whereas ligaments connect bone to bone), the fibular head (FH) or the upper aspect of the fibula, the patella (kneecap), joint capsule (JC)which is a fibrous structure that encloses the knee joint itself, and the iliotibial band (ITB) which is a thick band of fibrous connective tissue that runs from the hip to below the knee.

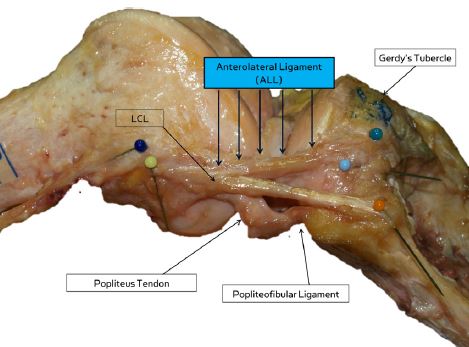

This view is completely dissected and the ALL is clearly delineated from other nearby structures.

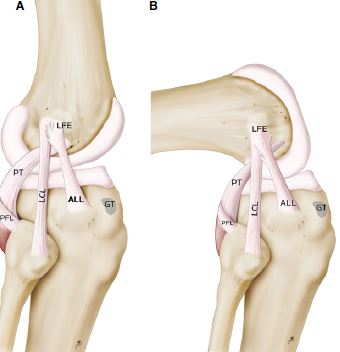

The illustration above more clearly shows the relationship and insertion points of some of the ligaments and tendons in the knee.

Based on the location of the ALL and some evidence from bone fracture patterns in some types of knee injuries, Claes and colleagues propose that the ALL has a role in stabilizing the knee during internal rotation, but they do not attempt to address that hypothesis in this paper.

No comments

Be the first one to leave a comment.