Obesity and the Immune System

The paper: Takagi, K. et al. (2013) Anti-ghrelin immunoglobulins modulate ghrelin stability and its orexigenic effect in obese mice and humans. Nature Communications 4:2685. doi:10.1038/ncomms3685

Subject areas: Physiology

Vocabulary:

orexigenic – something that increases the appetite for food.

anorexia nervosa – an eating disorder characterized by an obsession with maintaining an extremely low body weight for the patient’s height, build, and age. Patients often starve themselves or exercise obsessively to lose weight or prevent weight gain.

—–

This article is a summary of a recent primary research paper intended for high school teachers to add to their general knowledge of current biology, or to supplement their lessons by showing students the kinds of projects that current biological research addresses.

—–

Obesity continues to be a serious health problem in the developed world, and in the United States in particular. While some of the causes of obesity are related to personal decisions and self-controllable actions, there are also physiological factors that can drive overeating. Ghrelin and leptin are hormones that influence food intake: leptin suppresses appetite while ghrelin increases it. In this paper, Takagi and colleagues have demonstrated a mechanism by which the body can alter its response to ghrelin.

Although obesity is often linked with increased hunger and eating, the concentration of ghrelin in the blood plasma is not always increased. One interpretation is that somehow the same level of ghrelin is signaling greater levels of hunger than normal. This would be consistent with the observation that when ghrelin is given to obese human subjects, it stimulates eating more than the same amount of ghrelin given to lean subjects.

What is known

Ghrelin is a peptide (a small chain of amino acids; essentially, a really small protein) hormone secreted by the stomach. It is active upon secretion, and becomes inactive when it is broken down by enzymes. An earlier study showed that in obese subjects, there were lower levels of the inactive breakdown product of ghrelin than in lean subjects, while levels of active ghrelin remain the same. This could indicate some mechanism to increase the stability of ghrelin to prolong its activity.

On a seemingly separate note, a recent paper identified immunoglobulins (antibodies) to ghrelin in both healthy subjects and patients with anorexia nervosa. Antibodies are usually made by the immune system to recognize and repel foreign molecules/organisms. However, sometimes, autoantibodies can be made that recognize molecules produced by the body itself. It was shown that artificially stimulating ghrelin production in rats also leads to an increase in immunoglobulins (Ig) to ghrelin. In at least one study (Zorrilla et al, 2006), inducing the formation of antibodies to ghrelin caused a decrease in body weight.

What they did

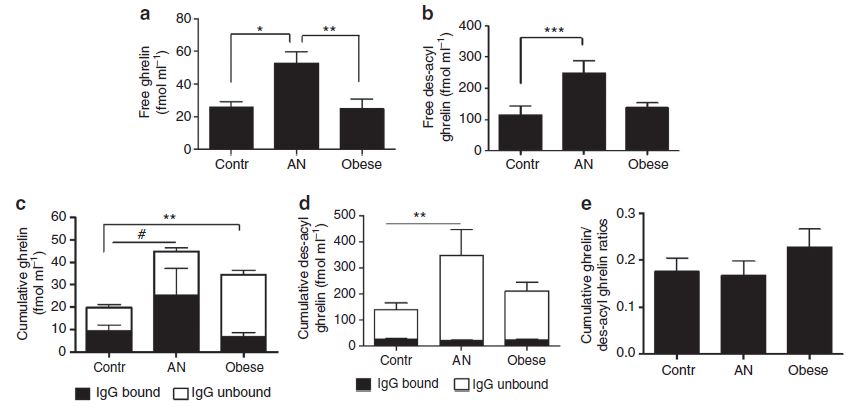

The first step in the investigation was to measure the ghrelin and des-acyl ghrelin (the inactive degraded form of ghrelin) in lean patients, obese patients, and patients with anorexia nervosa (AN). The figure below shows the amount of (a) ghrelin in the blood plasma and (b) the amount of inactive des-acyl ghrelin. There is no difference between control and obese patients, but there is a clear increase of both ghrelin and des-acyl ghrelin levels in the blood of AN patients. The researchers then extracted Ig-bound ghrelin or des-acyl ghrelin from the blood plasma. Interestingly, when looking at (c) total ghrelin levels (both Ig-bound and unbound), there is again a significant difference between control and AN patients, but an even larger difference between control and obese patients. Finally, (e) shows that there is a slightly higher but not significantly different ratio of ghrelin to des-acyl ghrelin in obese patients compared to either control or AN patients.

The investigators then did several experiments to determine the affinity characteristics of the anti-ghrelin antibodies and found that antibodies from obese patients dissociated more slowly after binding onto ghrelin than the antibodies from control or AN patients. Other biochemical tests showed that IgG from obese patients reduced degradation of ghrelin when incubated in blood plasma.

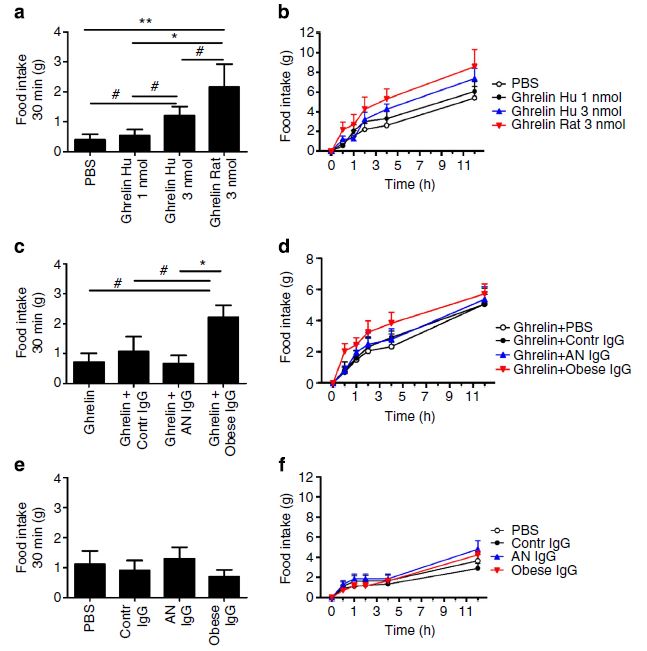

Takagi et al then injected the ghrelin into rats along with one of the various anti-ghrelin antibodies that they had characterized. Unsurprisingly, human ghrelin was not as effective as rat ghrelin at inducing food intake by the rats, but it is still bioactive enough to study in this experimental system. The graph below shows the result. Results from injection of ghrelin alone are shown in (a) and (b). Jumping to the bottom, injection of the different antibodies alone without ghrelin is shown: there is no significant difference from control. Finally, when both IgG and human ghrelin are injected, there is a clear increase in food intake by only those rats who had the ghrelin with the IgG from obese patients.

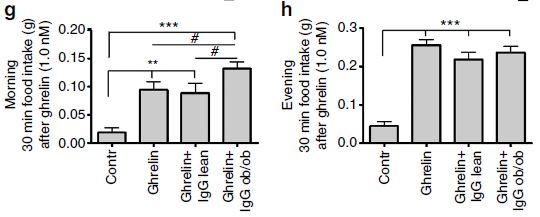

Finally, the the ghrelin and IgG combinations were taken from normal and ob/ob (obese) mutant mice with a mutation in the leptin gene. Although the injection of ghrelin and IgG taken from obese mice caused significant weight gain, there was no change in the proportion of fat to lean mass. Other interesting anomalies from injections of ghrelin and anti-ghrelin IgG of ob/ob mice into normal mice are that the effect appears to be time- or light- dependent.

What it means

There are a few ideas to make note of here if you are talking about this article with students. One is that obesity clearly affects many seemingly unrelated systems in the body, an in particular the immune system. Interestingly, the finding here that anti-ghrelin antibodies from obese animals/humans have a stabilizing and positive effect on ghrelin activity is in contrast with a previous finding that anti-ghrelin antibodies in mice block their activity. This is not necessarily a contradiction, as there could be differences in exactly where and how tightly each antibody binds so that one might cover the binding site so the ghrelin cannot activate the ghrelin receptors, while the other binds in a way that prevents breakdown, but does not affect receptor binding. Clearly it is a matter for further investigation. Second, one of the difficult problems in treating obesity is the overriding of a negative-feedback loop (e.g. as fat stores rise, leptin is secreted, which then limits appetite and cuts down fat storage to maintain a steady level of fat storage). When some level of obesity is reached, that control system is overridden by a positive-feedback loop in which the stabilizing anti-ghrelin antibodies are made, which increases ghrelin activity, which increases appetite, increasing obesity, and coming back around, increasing the stabilizing antibodies, quickly spiraling out of control. Incidentally, this is an example of why in biology, there are many more examples of negative-feedback control than positive-feedback.

On a more positive note, this study does suggest that since not all anti-ghrelin antibodies modulate ghrelin in the same way, it may still be possible to generate treatments for obesity by triggering an autoimmune response to ghrelin in a particular direction. Alternatively, perhaps temporarily interfering with the immune system of obese patients may allow ghrelin to function more normally again to help the patient eat less.

No comments

Be the first one to leave a comment.