Burning Habitats with Positive Results

The paper: Bird, R.B. et al. (2013) Niche construction and Dreaming logic: aboriginal patch mosaic burning and varanid lizards (Varanus gouldii) in Australia. Proc. R. Soc. B 280 (172):20132297 doi: 10.1098/rspb.2013.2297

Subject areas: Ecology

Vocabulary:

Goanna – a large Australian lizard also known as the sand monitor. They average 1.4 meters in length and up to 6 kg in weight. Goannas are carnivores, eating small mammals, insects, and other smaller lizard species.

—–

This article is a summary of a recent primary research paper intended for high school teachers to add to their general knowledge of current biology, or to supplement their lessons by showing students the kinds of projects that current biological research addresses.

—–

At first glance, the title generated some skepticism: was this going to be a pseudoscientific article to confirm an aboriginal religion/belief system? Not at all. Instead, the article explores a seemingly paradoxical ecological relationship between anthropogenic hunting and habitat destruction and increases in the native animal (lizard) population. It so happens that this relationship is recorded in the Dreaming of various Australian aboriginal groups. The Dreaming is a kind of combination oral history, mythology, belief system, and law/rules of society. In some forms, the Dreaming also includes details that could be from a naturalist’s notebook, including the kinds of species that live in certain habitats, their life cycles, and migration patterns. The Dreaming also happens to recommend hunting and burning (of small areas to drive animals in a certain direction for easier hunting) as necessary to the preservation of the hunted animals’ continued existence.

Historical Perspective

For tens of thousands of years, there have been nomadic hunter-gatherers foraging the desert grasslands of Australia. A common hunting strategy, especially during the cooler seasons when reptilian prey such as the sand monitor lizard spends much more time in their burrows, is to drive the animals out using fire. Because the aboriginal hunters used relatively small spot fires, this would lead to a patchwork environment of areas in different stages of recovery from the fires. Because different plant species arise at different times after an area has been cleared by fire, this leads to plant heterogeneity and herbivore/small prey heterogeneity which helps support the larger predators that the human hunters often hunt.

In some parts of Australia, this cycle was broken as a large efflux of aboriginal peoples gave up their traditional ways and moved out of the desert to small towns and missions along the desert borders between approximately the 1930s and 1970s. Without human hunting and burning, the number and types of animals in the desert dropped significantly. In fact, at least ten native species went extinct, another 40-50 experienced steep population drops, and there was an increase in lightning-ignited fires that covered giant swaths of the grasslands. Previously, the spread of such lightning fires would have been limited by the vegetation-free area that been spot-burned by the nomadic hunters. In 1984, the Martu people returned to the Little Sandy Desert of western Australia, and began to re-establish their traditional hunting and foraging patterns. Since that time, landscape heterogeneity has increased, and so have the fauna.

Following the Sand Monitor

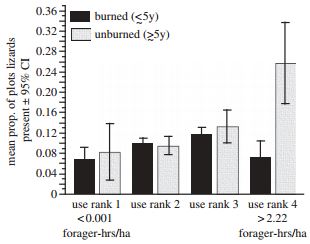

For this paper, the authors followed a Martu group to observe effects on Varanus gouldii, the sand monitor. The Martu hunt these lizards for food, and as noted above, in the cooler months, use small fires to drive the lizards from their burrows. Since the Martu typically forage from and return to a central community site, areas closer to the community are more frequently hunted, while areas further away are less visited by the Martu. Sectors of the desert could then be designated based on Martu usage: from 1 (least used) to 4 (most used). The researchers would typically follow along with Martu hunters with a GPS and make note of the numbers of lizards observed, and whether the lizards were in a patch of land that had been recently (up to 5 years prior) been burned or had not been burned in at least 5 years.

The graph above shows a surprising relationship. Ignoring the difference between black and white, there is a significantly higher density of lizards in the areas with the highest amount of human activity. There is a trend of higher lizard numbers from rank 1 to rank 3 usage, but at rank 4, there is a big jump in lizards found in the unburned areas. This is not true of the recently burned areas: there is a peak in lizard occupancy of burn areas in rank 3, but there is much less variation than in the unburned areas. The lower lizard counts in the burned areas are likely because with sparser and shorter vegetation, both the lizards and their prey are more exposed than in the unburned areas. By the same token, there should be more lizards in the border areas between burned and unburned spots where lizards could hide in the deeper brush while watching for prey in burned clearings.

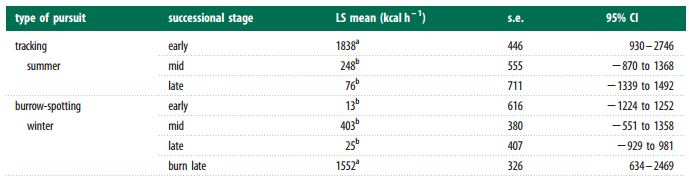

Finally, in partial explanation of why the Martu use the small fires to drive animals from their burrows (something they only do in the late winter), the table below shows the average results of foraging (LS mean) given in kcal/hr. In other words, the amount of energy gained from the animals they are able to hunt down per amount of time spend hunting them. Compare the numbers for late winter foraging and late winter foraging using burning. Burning provides 62 times as much as hunting without the use of fires.

This paper presents compelling evidence that human manipulation of the natural environment is not necessarily a bad thing. Most of the time, we think of loss of habitats and subsequent loss of species when humans modify an area, particular in as destructive a manner as burning. However, there are clearly ways of doing so that not only do not harm the wildlife, but in fact help to maintain their presence in a given area. The surprising finding that so many species dwindled when man removed himself from the Australian desert calls for closer analysis of the interplay between human activity and the living environment.

![By Matt Clancy [2012, CC-BY-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons](http://www.axopub.com/wp01/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Sand_Monitor_Varanus_gouldii_8236023719.jpg)

No comments

Be the first one to leave a comment.