Gold doesn’t grow on trees, does it?

The paper: Lintern, M. et al. (2013) Natural gold particles in Eucalyptus leaves and their relevance to exploration for buried gold deposits. Nature Communications 4:2274. doi:10.1038/ncomms3614

Subject areas: Biogeochemistry, Botany

Vocabulary:

eucalyptus – probably best known as the primary food for koalas. Eucalyptus actually refers to a Myrtle family of trees and shrubs. Eucalyptus trees are one of the most common trees in Australia. Most of the over 700 species of Eucalyptus are found in Australia. Adult forms of eucalyptus are generally either low shrubs or very tall trees – in fact, members of the Eucalyptus family are four of the ten tallest trees in the world.

—–

This article is a summary of a recent primary research paper intended for high school teachers to add to their general knowledge of current biology, or to supplement their lessons by showing students the kinds of projects that current biological research addresses.

—–

Previous studies of gold found in samples of natural vegetation were complicated by the possibility of surface contamination, and while there have been studies of gold uptake by plants, most of them were done in a laboratory setting on plants that are not common near gold deposits in Australia. The eucalyptus plant, on the other hand, is very well suited as a potential indicator plant. It is found in areas with gold deposits, and it has a very deep root system, enabling it to sample the earth as far as 40 meters below the surface – important to survive in arid environments and droughts. In particular, it is native to both of the sites used in this study: the Freddo gold deposit and the Barns Gold Prospect, though the trees at Barns are generally smaller (~5m tall) than those at Freddo (~10m).

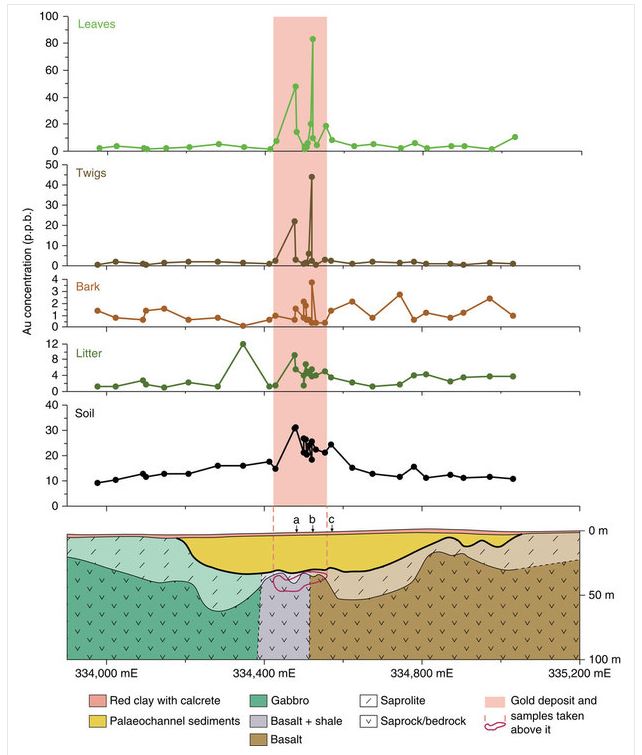

Without a definitive idea of where gold might be transported and stored in a plant, the first order of business is to determine the parts of the plant with the highest gold content. The graphs here show a much stronger spike in gold content in the leaves and twigs than in other parts of the tree. Based on its mass alone, the tree trunk is a major store of gold in the tree, but with respect to concentration, the leaves have the highest measured concentration of Au (80 parts per billion) compared to just around 0.5 ppb for the tree trunk samples.

The graphs show measurements from trees at locations at varying distances from the gold deposit as shown in the cross-sectional linear map below the graphs, with a total sampling distance of approximately 1.3 km. The data clearly shows that the gold content in the leaves and twigs over the deposit is significantly higher than the background levels of gold found in trees near but not in contact with the gold underground.

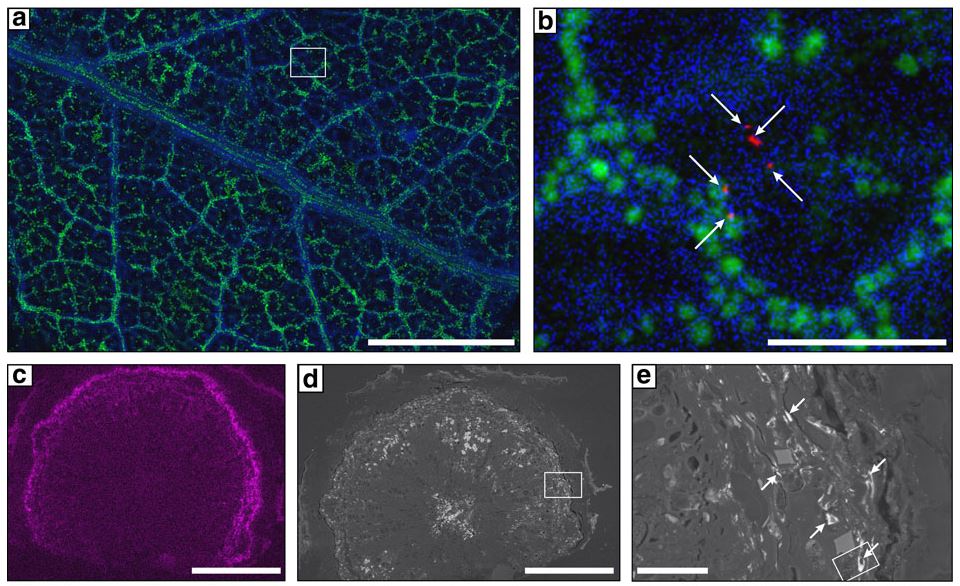

To confirm that the gold is in fact incorporated in the tissues and not some kind of surface contamination, samples of the leaves were examined with a particle accelerator and X-ray fluroescence microprobe (a and b, below) and by scanning electron microscopy (b-e). Note that the SEM photomicrographs are from lab-grown twig sections, not the natural samples. Interestingly, the liquid exudate that the eucalyptus leaf secretes at night is also enriched in soluble gold in those trees located over the Barns gold deposits, as much as 20 times higher than background samples from trees just 800 meters away. This could explain the slight enrichment of gold in upper soil layers but not intermediate layers above the gold deposits. The gold could be left on the leaf surfaces as the exudate evaporates, and then washed onto the underlying soil when it rains.

Because the deposits studied here are in a tectonically stable area, it is unlikely that pressurized pumping of gases or water carrying gold nanoparticles is a significant mechanism of gold transport to the surface. Instead, the model proposed by Lintern and colleagues has the gold (as gold ions in water) transported up by the deep roots of the eucalyptus through the tree to the leaves and twigs. Depending on the climate, the gold may be exuded onto the leaf surfaces, where it can be concentrated and/or crystallized by evaporation of the water. Rain may wash some of that down to the ground, and the surface soil may also pick up gold from falling leaves and twigs. All of this is consistent with the levels of gold found in the trees and soil over the gold deposits studied. Further, the broader distribution (compared to the eucalyptus trees) of gold in the upper soil layers can be explained by intermittent erosion processes, carrying some of the gold away from the site.

No comments

Be the first one to leave a comment.