Pheromones Prevent Juvenile Sex

The paper: Ferrero, D.M. et al. (2013) A juvenile mouse pheromone inhibits sexual behaviour through the vomeronasal system. Nature 502: 368-371. doi:10.1038/nature12579

Subject areas: Physiology, Animal Behavior

Vocabulary:

Pheromone – chemicals produced by some animals (insects, most vertebrates except birds) to communicate with others of the same species. They are usually volatile and airborne, but can also be left on solid surfaces that the animal contacts. Although often associated with sexual response, pheromones are also used to signal other situations, such as danger, or the presence of food.

—–

This article is a summary of a recent primary research paper intended for high school teachers to add to their general knowledge of current biology, or to supplement their lessons by showing students the kinds of projects that current biological research addresses.

—–

Mammals, including humans and laboratory mice, can communicate through chemical signals. When these signals are volatile (in the sense that they can evaporate and become airborne at normal environmental temperatures), they are usually sensed by either the olfactory system or the vomeronasal system, or both. When we think of “normal” smells, they are mediated by the olfactory system. On the other hand, when a chemical signal that is not perceived as a distinct smell causes a change in behavior or just a gain of information, that is being mediated by the vomeronasal system. For a long time, it was assumed that the two systems were completely separate, though both are usually located in the nose of mammals. However, it has become clear that there are pheromones that can activate both systems.

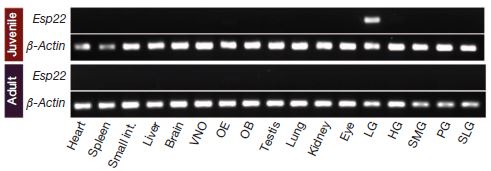

This research group is interested in pheromones, and they surveyed potential pheromones from different tissues, including the lacrimal gland, which produces pheromones that can be found in tears. When they examined some of these across different sexes and ages, the researchers noticed that one, called ESP22, was produced only by juveniles, but not in adults nor neonates. Its expression peaks around 2-3 weeks of age and drops sharply after 4 weeks, which is close to puberty. As you can see in the gel shown below, Esp22 is expressed only in the lacrimal gland of juveniles, not in any other tissues.

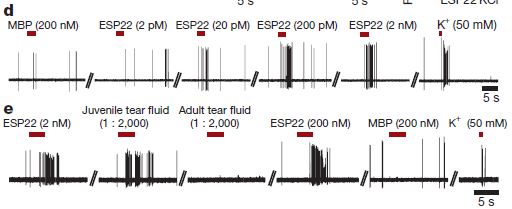

At this point, Ferrero and colleagues knew that ESP22 was genetically and biochemically similar to other pheromones and was produced by a gland that produces other pheromones, but they had no evidence that ESP22 was actually a functional pheromone, conveying some kind of signal to other mice. So, the next order of business was to test ESP22 on the vomeronasal organ. They prepared a solution of ESP22 and introduced it onto the vomeronasal organ. Using electrodes to record the electrophysiological response of individual vomeronasal neurons, they found (d and e, below) that as about 20 picomolar concentration of ESP22, they could detect neuronal excitation above the control MBP (a protein that is known to have no effect on the neurons). Furthermore, this effect was similar to juvenile mouse tears, but adult tears elicited no neuronal activity.

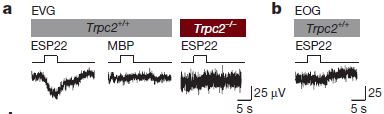

They also found that the electrical activity was dependent on a neuronal ion channel, Trpc2. In the figure below, the red Trpc2-/- indicates an experiment in which ESP22 was applied to the vomeronasal organ of a mutant mouse in which Trpc2 was knocked out. As you can see, there was no effect. Also, in part (b) below, the researchers also show that in a normal mouse, ESP22 does not excite the olfactory epithelium. Now there is good evidence that ESP22 is a pheromone that acts on the vomeronasal organ.

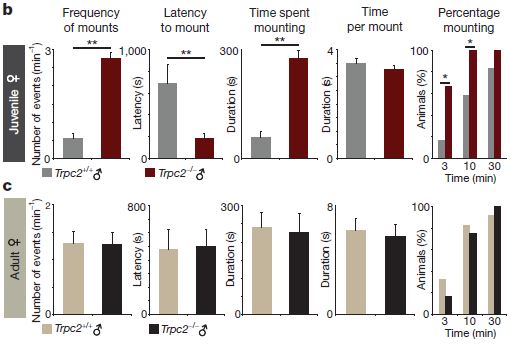

What exactly does it do, though? The initial clues came from the Trpc2-/- knockout mice. It was already known that in these mice have severe problems with sex recognition between adults. Since ESP22 is a juvenile pheromone, male Trpc2-/- mice were observed in the company of juvenile mice. The result was striking, as the authors themselves put it. There was a significant increase in sexual behavior by the Trpc2-/- mice towards juvenile females (b, below. grey is wild-type, red is Trpc2-/- knockouts). Normal wild-type mice very rarely attempt to mount juveniles. In contrast, wild-type and Trpc2-/- males attempt to mount adult females with roughly the same frequency (c, below).

Ferrero et al have discovered a new pheromone, ESP22. More significantly, it is the first juvenile-specific pheromone demonstrated, and has the function of inhibiting sexual behavior in male mice. The pheromone acts only through the vomeronasal organ, without a contribution from the olfactory system, and involves the ion channel, Trpc2.

No comments

Be the first one to leave a comment.