Fossilized Mosquito with Blood Discovered!

The paper: Greenwalt, D.E. et al. (2013) Hemoglobin-derived porphyrins preserved in a Middle Eocene blood-engorged mosquito. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. (USA) doi:10.1073/pnas.1310885110

Subject areas: Paleontology

Vocabulary:

Eocene – a geological epoch from 56 million years ago through 33/9 million years ago. It is a part of the Cenozoic Era, and the oldest fossils of modern mammals come from this time period. This is after the Cretaceous-Paleogene Extinction event that wiped out the non-avian dinosaurs.

—–

This article is a summary of a recent primary research paper intended for high school teachers to add to their general knowledge of current biology, or to supplement their lessons by showing students the kinds of projects that current biological research addresses.

—–

Although it is an iconic scene and idea from the 1993 blockbuster movie, Jurassic Park, no blood-filled mosquito had been discovered at that time, nor for that matter, for the nearly two decades since then. However, in this paper by Greenwalt and colleagues, there is finally good evidence for just that. Don’t expect live-dinosaur theme parks anytime soon, though. The movie mentioned, but downplayed the extent of DNA degradation. The fact is, the DNA in any specimen this old will have broken down well beyond any hope of getting sequence information.

Still, this is quite a discovery. The authors have studied a collection of fossilized mosquitoes from the Kishenehn Formation in northwestern Montana (USA). Noting the possibility that one was a female with an engorged abdomen (only females feed on blood), they tested the possibility that the substance inside the mosquito was blood. The specimen in question was not preserved in amber, as the movie mosquito was, but in sediment, or as it has become, sedimentary rock.

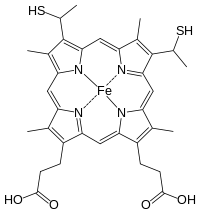

The key characteristic of blood is the presence of hemoglobin. Hemoglobin is an organic molecule with a structure known as a porphyrin ring that helps to hold an iron atom in place. The iron-porphyrin ring together is known as a heme group or structure. High concentrations of iron would not be expected anywhere in the mosquito but in a blood meal that it had ingested. However, iron can be deposited as part of the fossilization process, and has been shown in fossils from insects that do not feed on blood. So, what the researchers needed to look for is the presence of both iron (in excess of background) and porphyrin in the abdomen of this female, but not in other mosquitoes from the same area that clearly have not fed on blood.

The key characteristic of blood is the presence of hemoglobin. Hemoglobin is an organic molecule with a structure known as a porphyrin ring that helps to hold an iron atom in place. The iron-porphyrin ring together is known as a heme group or structure. High concentrations of iron would not be expected anywhere in the mosquito but in a blood meal that it had ingested. However, iron can be deposited as part of the fossilization process, and has been shown in fossils from insects that do not feed on blood. So, what the researchers needed to look for is the presence of both iron (in excess of background) and porphyrin in the abdomen of this female, but not in other mosquitoes from the same area that clearly have not fed on blood.

Keeping in mind that these are very tiny samples, and they certainly do not want to destroy them, the researchers used a technique calle ToF-SIMS. That stands for Time-of-Flight Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry. Basically, the ToF-SIMS machine shoots ions (charged atoms) at the sample. That knocks off particles from the sample surface, and those secondary particles fly off the sample and hit a detector. The time-of-flight and trajectory of the secondary particles from sample surface to the detector can be very precisely measured (nanoseconds, or billionths of a second). Because the velocities are proportional to mass:charge ratio, the identity of these particles can be determined.

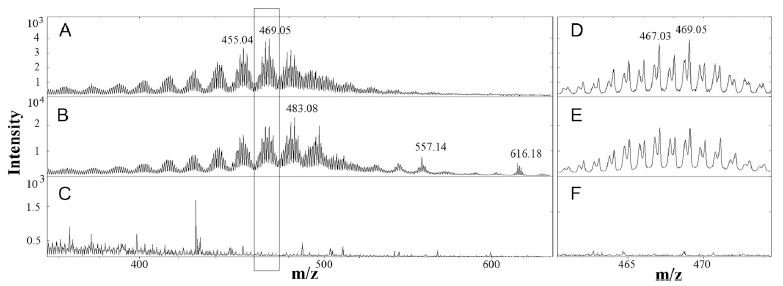

First, they needed to see what a heme looks like on the Tof-SIMS, and confirm that it exists in the female mosquito sample. The spectrogram below shows exactly that: (A) is the sample from the female mosquite abdomen and (B) is a sample of purified heme from pig blood. (C) is a sample from the rock right by the mosquito.

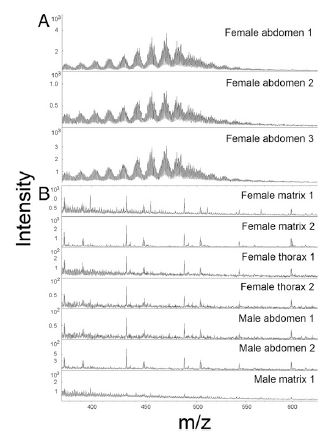

Now that they there is evidence of heme in the female abdomen, the researchers need to show that it is not a part of the mosquito itself, or these mosquitoes in general. The next figure shows that the heme ToF-SIMS signature is found at three different spots within the engorged female abdomen, but not in the matrix around it or in other parts of its body. It is also not found in a male of the same species found near the female.

There you have it: very strong evidence of a blood from an animal from some 46 million years ago, sucked up by a mosquito that was somehow trapped so quickly in sediment and fossilized that both mosquito and its last meal remained mostly intact. This is also the first evidence that the mosquito-like fossils that have been found actually might have behaved like modern mosquitoes and consumed the blood of other animals.

No comments

Be the first one to leave a comment.