Ant Wars

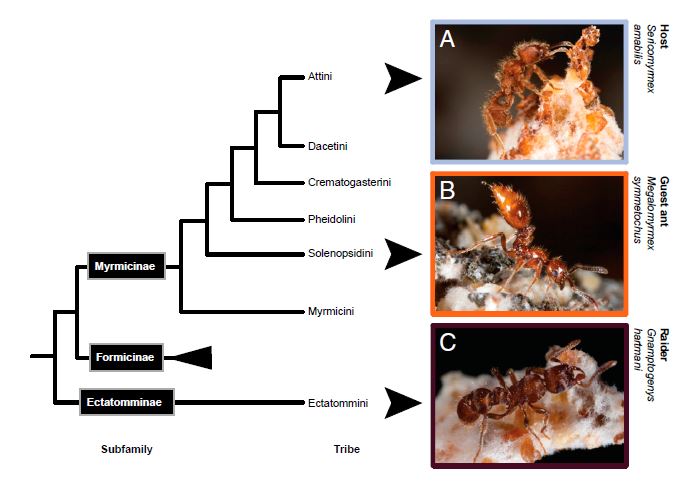

M sneakily infiltrates a colony of S, taking it over by imprisoning the S queen and eating the fungus farmed by S workers. G are raiders that directly assault the colony.

Subject areas: Ecology, Entomology

Vocabulary:

Parasite – An organism that lives in or on a host organism, and gets its food from, or at the expense of the host organism.

Social parasites – Social insects that parasitize colonies of other social insects.

The article:

Adams, R.M.M. et al. (2013) Chemically armed mercenary ants protect fungus-farming societies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (USA). doi:10.1073/pnas.1311654110

What Is Already Known

There are three kinds of social parasitism in ants, in which one ant species takes over and coexists with the colony of another species.

In temporary social parasitism, the parasite queen gains entry into the host colony, kills its queen, and has the host colony’s workers accept it as the new queen. They then take care of the parasite queen and her eggs, which hatch parasite workers that eventually kill off all of the host ants (which is why the parasitism is considered temporary). Eventually the colony contains just the parasitic species.

Another kind of ant social parasitism is the permanent inquilines. Here, the host queens are generally left alive, and the host colony continues to produce workers and more or less behave normally. The parasite queen does lay eggs that are taken care of by the hosts, but they do not develop into workers – just reproductive forms.

Finally, the slaver or slave-maker parasites begin their parasitism like the temporary parasites, infiltrating a colony and replacing its queen. However, they also aggressively raid other colonies, not necessarily to parasitize them, but to kidnap workers and turn them into their own slave-workers. The colony always has multiple species, although not all slave-maker parasites use slaves to the same extent.

The Question

Megalomyrmex symmetochus is a permanent inquiline type parasite that parasitizes colonies of Sericomyrmex amabilis, which is a fungus-growing ant (the fungus is food for them). Unlike many other permanent inquilines though, M. symmetochus does hatch its own workers. Interestingly, they do not kill the members of the host colony. Why would such a relationship evolve between these two species?

The authors considered some possibilities. Perhaps the host ants are unable to properly feed the parasite larvae? Maybe the host ants are not fully dominated and keep on trying to retake the colony and kill the parasite queen? Or perhaps the parasite workers are an army used to take over other colonies? The parasites adults eat the same fungus as the hosts, so it seems likely the larvae would have little problem. The host workers are unlikely to pose much threat of a (re)takeover, since their stings are vestigial and ineffective, while the parasite workers are well armed. And finally, there is no evidence that the parasites invade other colonies by full-scale assault.

What They Found

Having ruled out those possibilities, Adams et al considered another possibility: the parasite workers were an army, but a purely defensive one, that guarded both the host and parasite ants of the colony from a third species – predatory raiding ants. There was evidence of such raiding ants in the wild attacking colonies of Sericomyrmex (host species), so it seemed possible.

The scientists tested this idea in the lab, testing Sericomyrmex colonies with and without Megalomymex parasites, against an attack by a force of Gnamptogenys hartmani, which is the predator species. Some of their results confirmed their hypothesis, but they also found out something surprising. For simplicity, we’ll refer to S. amabilis as “host”, M. symmetochus as “parasite”, and G. hartmani as “raider”.

To get a baseline assessment of how the ants fared individually, they set up dishes pitting one raider ant against 2-8 host or parasite ants. The host ants were only able to defeat the raider when they had a group of 8, and even then, they did not prevail every time. In contrast, most of the time the parasite ants were able to kill the raider even with a group of 2.

In the mixed-group situation, not surprisingly, having a greater number of parasite ants with the host ants in a colony led to a stronger defense. Interestingly, it appears that when in mixed groups, the parasite ants take the lead in the fight, while the host ants fight less. In a cool bit of luck, the researchers can tell this very easily because parasite ants fight by injecting venom with a stinger, while host ants fight by biting and chewing off the attackers’ extremities. As parasite numbers increased, the number of dead raiders with antennae and legs chewed off decreased, indicating they were no longer being attacked by the host ants.

[Side note – the venom does not just kill raider ants, it also seems to disorient them and cause them to attack each other! Pretty cool, right?]

These experiments provided strong evidence supporting the hypothesis that the parasitic worker ants were essentially a defensive army for the colony. Because it is well known that ants signal each other chemically, the researchers did one more test, and found out something interesting. If raider ants were given a choice of colonies, they would strongly prefer host colonies that had not been parasitized, even without seeing or fighting a single predator. It turns out that the venom of the Megalomyrmex parasites are volatile enough that they can be detected in the air near the colony, and that was enough to ward off raiders!

No comments

Be the first one to leave a comment.